2c) The legend about Bouffier - the

original text - translation

Book "The man who planted

trees", original French:

"L'homme qui plantait des arbres" [1]

Jean Giono

The man who planted trees

Edition BeQ [p.1]

Jean Giono

The man who planted trees

Electronic Library of Quebec

Classic collection of the 20th century

Volume 49: Version 1.01

http://permaculteur.free.fr/ressources/Giono-arbres.pdf

[p.2]

In order for a person's character to reveal truly

extraordinary qualities, one must be fortunate enough to

be able to observe his actions over many years. If the

actions contain no egoisms, if the guiding idea of

generosity is unprecedented, if one can be absolutely

certain that no reward has been sought anywhere through

the actions, and if these actions have left visible traces

in the world, then we are undoubtedly faced with an

unforgettable character. [p.3]

The walk in the barren Southern Alps - abandoned and

dilapidated villages

About forty years ago [in 1913], I walked for a long time,

on completely unknown heights, in this very ancient region

of the Alps that stretches as far as Provence.

This region is bordered in the southeast and south by the

central section of Durance River between the locations of

Sisteron and Mirabeau; in the north by the upper part of

the department Drôme, from the beginning as far as to the

village of Die; in the west by the plains of the Comtat

Venaissin and the hills of Mont Ventoux. It covers the

entire northern part of the department of Basses-Alpes,

the south of the department of Drôme and a small enclave

of the department of Vaucluse.

Bouffier's sphere of action from

Durance River to Drôme River - with the marking of the

forest area [2,3]

Durance River Durance at Manosque

[4] - Durance Valley in High Provence (Haute Provence)

[5] - Drôme River at Saillans below the location of

Die [6] -River Drôme with kayakers

[7]

When I started my long walk in these barren areas, they

were naked and there were monotonous moors, at an altitude

of about 1200 to 1300 meters. Only wild lavender grew

there [p.4].

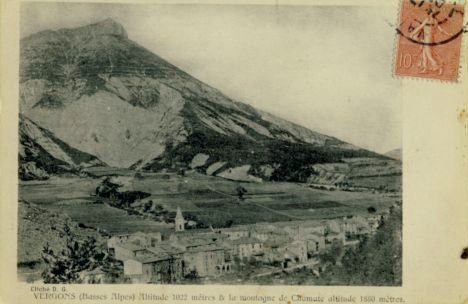

Lavender field in the Drôme valley

[8] - the location of Vergons around 1910 - the mountain

is practically WITHOUT forest [9]

I crossed this region in the broadest sense and after

three days of walking I found myself in a bleak situation

without example. I camped next to an abandoned village

that was abandoned and half dilapidated, like a skeleton.

I hadn't had any water since the day before and had to

find some. These houses, although in ruins, like an old

wasp nest, made me think that there must have been a

fountain or well there in the past. There was a well, but

it was dry. The five to six houses, without roofs, gnawed

to pieces by wind and rain, the small chapel with its

collapsed bell tower, could only be seen in it's outlines.

All this was arranged in the same way as in other villages

where there was still life. But here all life had

disappeared.

It was a beautiful day in June with lots of sunshine, but

in this area without shelter so close to the sky the wind

blew with unbearable brutality. His rumbling in the ruins

of the houses was like a wild animal that was protesting

against being disturbed during his meal.

The shepherd, his farm, his well

Country house in Provence [10] - A

shepherd with a flock of sheep in Castellane going up to

the Alps, High Provence (Haute Provence) [11]

I had to leave my campsite. Five hours later [p.5] I had

still not found any water and there was no hope of finding

it. Everywhere the same drought was prevailing, the same

woody grasses were dominating. Then I saw something like a

little black figure in the distance. I thought it was the

trunk of a lonely tree. By chance I approached it. It was

a shepherd. With him about thirty sheep lay on the warmed

up ground.

He let me drink from his drinking bottle, and a little

time later he led me to his sheepfold, which lay in a

depression of the plateau. He drew his water from the well

- excellent water - from a natural, very deep hole, over

which he had installed a rudimentary winch.

This man spoke little. This is the habit of the loners,

but we felt full of confidence and trust in this place. It

was an unusual place in this region where hardly anything

grew. He did not live in a hut, but in a real stone house,

where one could see very clearly how his work worked

[p.6].

He had renovated a ruin he had found there. The roof was

solid and waterproof. The wind hit the house and made a

rushing sound on the tiles like on a beach.

His household was fine, his dishes were washed, his

parquet floor was swept, his gun was greased; his soup

cooked on the fire; I noticed then that he was also

freshly shaved, that all his buttons were tightly sewn,

that his clothes were patched with meticulous care so that

the repairs were invisible. [Thei were not so invible,

so...]

He shared his soup with me, and when I made a joke about

smoking, he said he didn't smoke. His dog, who was as

quiet as he was, was benevolent, without malice.

It was immediately clear that I would spend the night

there; the next village was still more than a day and a

half away on foot. And I was also very familiar with the

character of the few villages in this region. There are

four or five scattered places here [p.7], far apart on the

sides of these heights, in the white oak forests at the

ends of the trafficable roads. They are inhabited by

lumberjacks who produce charcoal. These are places where

people do not have a good life. Families who have to live

together in this extremely harsh climate, both in summer

and in winter, spoil their selfishness in a vacuum. The

result is an inappropriate ambition, a constant desire to

flee from this place. The men bring their coal with their

trucks into the city and then return. The strongest people

break under this eternal Scottish shower. Women are

planning revenge actions. Everything is in competition,

both in the sale of the coal and on the bank in the

church, because of the virtues that fight each other,

because of the vices that fight each other, and because of

the general hustle and bustle of vices and virtues, there

is no rest. Moreover, the wind also irritates the nerves.

There are epidemics [p.8] with suicides and many cases of

madness, it is almost always ending fatally.

Sorting acorns - making holes with an iron rod -

setting acorns

Acorns with oak leaves [12] - Mount

Ventoux (Mont Ventoux), karst and woods, 1909m above sea

level [13]

The shepherd who did not smoke fetched a small bag and

spread a pile of acorns on the table. He began to examine

them one by one with great attention and separated the

good ones from the bad ones. I smoked my pipe. I offered

to help him. He told me it was only his business. Indeed,

given the care he has taken in this work, I did not insist

on helping. That was our whole conversation. When he had a

heap of quite large acorns on his good side, he counted

them in packs of ten. He still eliminated small acorns or

those that were slightly torn, as he examined them very

carefully. When he had a hundred perfect acorns in front

of him, he stopped and we went to bed.

This man's company gave peace. The next day I asked him

permission to rest with him all day long. He found it

natural. Or more precisely, he gave me [p.9] the

impression that nothing could bother him. This break was

not absolutely necessary for me, but I was fascinated and

wanted to learn more from him.

[The next morning] he let his flock out and led it to the

pasture. Before he left, he soaked the small bag [with the

acorns] in a bucket of water, where he had put the

carefully selected and counted acorns the night before.

I noticed that as a stick he carried an iron bar which was

as thick as his thumb and about one and a half meters

long. I was rested and walking parallel to him on a

street. The pasture of his animals was in the background

in a gorge. He left the small herd in the care of the dog

and came to me. I was afraid that he would blame me for my

indiscretion, but not at all: that was his way and he

invited me to go with him when I had nothing better to do.

He went two hundred meters further, up the hill.

When he reached the spot where he wanted to go, he began

to stick his iron rod into the ground [p.10]. He made a

hole in which he put an acorn, then he closed the hole

again. He planted oaks. I asked him if the land belonged

to him. He answered no. Did he know who owned it? He did

not know. He assumed it was community land, or maybe it

belonged to people who didn't care. He didn't care to know

the owners. He simply planted a hundred acorns with the

utmost care.

10,000 out of 100,000 oak trees grow

Haute-Provence, young oak forest on

white karst soil with Mont Ventoux in the background

[14]

After lunch he started sorting his seeds again. I think my

questions weren't stupid because he answered them. For

three years he has been planting trees in this solitude.

He had planted a hundred thousand of them. Of the hundred

thousand, twenty thousand had risen. Of these twenty

thousand, he still expected to lose half of them because

of animals eating them or because of other difficulties,

which could not be predicted even with the best

providence. So out of 100,000, 10,000 oaks remained, which

continued to grow in this place where there had been

nothing before [p.11].

Then I was worried about the age of this man. He was

obviously over fifty years old. Fifty-five, he said to me.

His name was Elzéard Bouffier. He had owned a farm in the

plains. He had realized his life there. He had lost his

only son and then his wife. He had retreated into

solitude, where he enjoyed living slowly, with his sheep

and his dog. He had realized that this land would die

because of lack of trees. Since he had no very important

professions, he decided to improve this situation.

At that time, despite my young age, I knew how to deal

tenderly with the soul of a person living alone. But I

made a mistake. Especially at a young age I had to imagine

the future in terms of myself and a certain search for

happiness. I told him that these ten thousand oaks would

be great in thirty years. He simply replied to me that if

God gave him thirty more years of life, he would plant so

many more trees [p.12] that those 10,000 would be like a

drop in the sea.

He was already studying beech growing and had set up a

tree nursery near his house, the beech trees of the

beechnuts. The new trees, protected from the sheep by a

wire fence, grew nicely. And on soils with humidity

underground one should plant birches, he said to me. The

next day we separated.

First World War 1914-1919

The following year the First World War began, in which I

had to serve for five years. An infantry soldier could

hardly think of trees. To be honest, this very thing had

left no trace on me; I had taken it for a tick, like a

stamp collection - and forgot.

After the war [in 1919] I was at the top for a tiny

demobilization bonus, but I also had a strong desire to

get some fresh air. [p.13]

Without any preconceived opinion - except this - I

returned to this abandoned region.

The country had not changed. But behind the dead village I

saw in the distance a kind of grey fog that covered the

heights like a carpet. Already the day before I had

started to think again about this tree-planting shepherd.

"Ten thousand oaks", I thought to myself, "really do

occupy a very large space.

The new oak forest at Mont Ventoux - 11 kilometres

long, 3 kilometres wide

Mount Ventoux (Mont Ventoux) 02 [15]

The last five years [during the war], I had seen too many

people die, but I could not imagine the death of Elzéard

Bouffier so easily, especially since the men of twenty are

regarding the men of fifty as old men. He was not dead. It

was now even very green there. He had changed his job. He

had only four sheep left, but now he had about a hundred

beehives. The sheep kept feeding from his trees, so he had

to get rid of the sheep. He also told me (and I noticed

it) that he wasn't interested in the war at all. He had

continued planting without interruption. [p.14]

The oaks of 1910 were ten years old now and bigger than me

and him. The show was impressive now. I was literally

robbed of my voice, and since he did not speak, we spent

the whole day in silence in his forest. It was now divided

into three sections - a total of eleven kilometres long

and three kilometres wide. We celebrated together that

everything had come from this man's hands and soul -

without technical means. We understood that people in

areas other than destruction could be as effective as God.

He had followed his idea, and the beeches that reached my

shoulders and spread as far as the eye could see were the

witnesses. The oaks were thick and old enough not to be

eaten by animals anymore. If Providence now wanted to

cause damage, then hurricanes were necessary now. He

showed me some admirable birch groves that were five years

old [p.15], that is, they had been planted in 1915 - at

that time I had fought at Verdun. He had planted these

birches everywhere he suspected damp ground. Now they had

grown tenderly, at a young age, and were very determined.

Creation [with it's wars], by the way, was more in the

direction of encircling and chaining itself. He didn't

care; he stubbornly pursued his task, which was very

simple. But as I descended through the village, I saw

flowing streams that had always been dry since time

immemorial. It was the most amazing reaction operation I

have ever seen. These dry streams had once carried water

in ancient times. Some of these sad villages, which I

mentioned at the beginning of my story, were built on the

sites of ancient Gallo-Roman villages, of which there were

still traces. Digging archaeologists had still found

fishing hooks in these villages, which testified to the

fact that one could fish here once - that was not to be

thought of until the 20th century [p. 16].

People lived off the water tank.

The wind was also involved in forest formation and

scattered some seeds.

New sources, new water, new life

When the springs and water came back, pastures, meadows,

gardens, flowers and the reason for life appeared.

But the transformation was so slow that it became a habit

without causing any surprise. The hunters who went into

solitude hunting for hares or wild boars had noticed the

abundance of small trees, but they had attributed it to a

natural whim of nature. Therefore, no one has seen this

man's work. If they had suspected him, they would have

angered him. He was unexpected. Who in the villages and in

the administrations could have imagined such a

stubbornness being combined with the greatest generosity?

A crisis year: 100,000 maple trees are not coming

Since 1920, not one year has passed [p.17] without a visit

to Elzéard Bouffier. I have never seen him weak or

doubtful. And yet, God knows whether God will even push

this forward! I have not counted his setbacks. However, it

is easy to imagine that for such a success it was

necessary to overcome adversity; that in order to secure

the victory of such a passion one had to fight with

despair. During one year he had planted more than ten

thousand maples. They all died. The following year he let

be the maples to return to the beeches, which were even

better than the oaks.

In order to have a more or less precise idea of this

extraordinary character, we must not forget that he

practiced in complete solitude; so much so that towards

the end of his life he had lost the habit of speaking. Or

perhaps he didn't see the need for it?

1933: A forester - and a stone hut 12km away

Stone hut / shepherd's hut at Mount

Ventoux (Mont Ventoux) [16]

In 1933 he received a visit from an astonished forester.

This official ordered him not to make a fire outside for

fear that this natural forest might burn down [p.18].

"It is the first time", this naive man said, "that we see

a forest growing alone." At that time he wanted to plant

beech trees twelve kilometres from his house. To avoid the

round trip - because he was seventy-five now - he planned

to build a stone hut on the site of his plantations. Which

he did the following year.

1935: A forester boss and a picnic

Wooded Nesque Gorge near Mount

Ventoux [17]

In 1935 a real administrative delegation came to

investigate the natural forest. There came a big fish,

responsible for water and forest, a deputy, and a few

engineers. Many useless words were spoken. They decided to

do something, and fortunately nothing was done except the

only useful thing: to put the forest under state

protection and forbid anyone to come here to produce coal

from it. Because it was impossible not to be surprised by

the beauty of these healthy young trees. And this beauty

exercised its seductive power over the deputy himself.

[p.19]

I had a friend among the forester bosses who was part of

the delegation. I explained the secret to him. The

following week, one day, we both went in search of Elzéard

Bouffier. We found him at work, twenty kilometres from

where the inspection took place.

This chief forester was not my friend for nothing. He knew

the value of things. He knew how to be silent. I offered

the few chicken eggs I had brought as a gift. We shared

our three-hour picnic, and then spent a few more hours

quietly contemplating the landscape.

The side from which we came was covered with six to seven

meter high trees. I still remembered what the landscape

had looked like in 1913: like a desert..... The peaceful

and regular work, the living air of the heights, the

thrift and above all the serenity of the soul had given

this old man an almost solemn health. He was an athlete of

God. I wondered how many hectares [p.20] he would still

forest.

Before I left, my friend made a brief suggestion about

some of the tree species for which the area seemed

suitable. But he did not insist on it. "For good reason"

he told me afterwards, because "this man knows more than I

do." After an hour's walk - the thought had solidified

with him - he added: "He knows much more than anyone else.

He has found the Big Path to be happy!

It is thanks to this forester chief that not only the

forest, but also the happiness of this man was protected.

He had three forester guards appointed for this protection

and controlled and instructed them so that they remained

immune to all the bribes of the lumberjacks.

1939-1945: Short danger for the forest at Mont Ventoux

because of wood gas - but it was unprofitable

Wood gas car [18]

Only during the war in 1939, there was a serious danger

for this work. Cars were run on wood gas and there was

never enough wood. They began felling the oaks [p.21] of

1910, but where they were felling and carrying the trunks

out this was so far from any road network that the project

turned out to be very bad financially. The forest was kept

in peace. The shepherd had not seen anything. He was

thirty kilometers away continuing his work peacefully and

ignored the war of 1939, just as he had ignored the war of

1914.

June 1945: The transformation of the villages in the

Mount Ventoux region - example Vergons: fragrant breeze,

forest noise, rippling water, vegetable garden with

flowers

Vergons at around 1910 - the mountain

is practically WITHOUT forest [9] - Vergons of around

2010 ca.: ALL mountains have FOREST [19]

I last saw Elzéard Bouffier in June 1945. He was 87 years

old at that time. So I drove up the desert road again, but

now, despite the decay of the war, there was a bus

connecting the Durance Valley and the mountains. I hold

this relatively fast means of transport responsible for

the fact that I did not recognize the places of my first

walks any more. It also seemed to me that the route led me

to new places. I needed a village name to come to the

conclusion that I was still in this once ruined and

desolate region. The bus brought me to Vergons [p.22]. In

1913 this hamlet had ten to twelve houses and three

inhabitants [that might not be true, see the photo of

Vergons around 1910]. They were wild at that time, hated

each other and lived from hunting with traps: They were

more or less in the physical and moral state of the Stone

Age. Around the abandoned houses the stinging nettles grew

and devoured the houses. Their condition was hopeless. For

them it was only a matter of waiting for death: a

situation that hardly predisposed them to virtues.

But now everything had changed: Even the air. Instead of

the dry and brutal gusts that once welcomed me, a gentle

and fragrant breeze was blowing. From the height it was

roaring as if by the sea: it was the sound of the wind in

the woods. Finally, surprisingly, I heard the real splash

of water splashing into a well. I saw a newly built well

with plenty of water, and what really touched me the most

was a newly planted lime tree nearby, which had become

thick already after four years, an indisputable symbol of

a resurrection.

Moreover, in Vergons there were also traces of a [p.23]

new bustle which did not work without a certain hope. So,

hope had returned. The ruins had been removed, the

dilapidated walls had been demolished, and five houses had

been rebuilt. The village now [in 1945] had 28

inhabitants, including four young households. The new

houses, plastered with fresh plaster, were surrounded by

vegetable gardens in which vegetables and flowers,

cabbages and roses, leeks and snapdragons, celery and

anemones were growing, mixed but well-assorted. It was now

a place where people wanted to live.

From there I set off on foot. The war that we had just

brought behind us allowed only a limited life, but Lazarus

was out of the grave. On the lowered sides of the mountain

I saw small barley and rye fields in the grass; at the

foot of the narrow valleys were some green meadows.

In only eight years a change to health and swinging life

had been realized [p.24]. In the place of the ruins which

I had seen in 1913, there are today [1953] clean,

plastered farms that show a happy and comfortable life.

The old springs, fed by rainfall and snow from the

forests, began to flow again. The water was also somewhat

canalized. Beside each farm, in maple groves, the well

basins are overflowing and irrigating the mint growing

near the well. The villages were gradually rebuilt. New

population from the plains, where the land prices were

high, have settled in the countryside bringing new

youthfulness, movement and adventure. On the way there we

met well-fed men and women, boys and girls, who knew how

to laugh and who had become interested in farmer festivals

again. Considering the old population, which now lived in

a gentle existence, and the new arrivals, they were no

longer recognizable. All in all, more than ten thousand

people owed their happiness to the shepherd and tree

planter Elzéard Bouffier. [p.25]

Sisteron with Durance River [20] -

the location of Vaison la Romaine, Haute Provence [21]

- the location of Die with wooded mountain range,

Département Drôme [22]

When I consider that a single man, reduced to his simple

physical and moral resources, is enough to turn the desert

into a promised land, I find that despite everything, the

human condition is admirable. But when I consider all that

it took to achieve this result in terms of the consistency

of spirit and the determination of generosity, I have

great respect for this ancient peasant without culture,

who knew how to do this work worthy of God.

Elzéard Bouffier died peacefully in the Hospice of the

location of Banon in 1947. [p.26]

This is the 49th published book.

in the classical collection of the 20th century.

from the electronic library Quebec.

This electronic library of Quebek (Bibliothèque

électronique du Québec)

is the exclusive property of

Jean-Yves Dupuis. [p.28]